Foodborne illnesses are a substantial and largely preventable public health problem; before 2020 the incidence of most infections transmitted commonly through food had not declined for many years. To evaluate progress toward prevention of foodborne illnesses in the United States, the Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) of CDC’s Emerging Infections Program monitors the incidence of laboratory-diagnosed infections caused by eight pathogens transmitted commonly through food reported by 10 U.S. sites.* FoodNet is a collaboration among CDC, 10 state health departments, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS), and the Food and Drug Administration. This report summarizes preliminary 2020 data and describes changes in incidence with those during 2017–2019. During 2020, observed incidences of infections caused by enteric pathogens decreased 26% compared with 2017–2019; infections associated with international travel decreased markedly. The extent to which these reductions reflect actual decreases in illness or decreases in case detection is unknown. On March 13, 2020, the United States declared a national emergency in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. After the declaration, state and local officials implemented stay-at-home orders, restaurant closures, school and child care center closures, and other public health interventions to slow the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 (1). Federal travel restrictions were declared (1). These widespread interventions as well as other changes to daily life and hygiene behaviors, including increased handwashing, have likely changed exposures to foodborne pathogens. Other factors, such as changes in health care delivery, health care–seeking behaviors, and laboratory testing practices, might have decreased the detection of enteric infections. As the pandemic continues, surveillance of illness combined with data from other sources might help to elucidate the factors that led to the large changes in 2020; this understanding could lead to improved strategies to prevent illness. To reduce the incidence of these infections concerted efforts are needed, from farm to processing plant to restaurants and homes. Consumers can reduce their risk of foodborne illness by following safe food-handling and preparation recommendations.

FoodNet conducts active, population-based surveillance of laboratory-diagnosed infections caused by Campylobacter, Cyclospora, Listeria, Salmonella, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), Shigella, Vibrio, and Yersinia reported from 10 sites covering approximately 15% of the U.S. population (approximately 50 million persons per U.S. Census Bureau estimates in 2019). Bacterial infections are defined as isolation of bacteria from a clinical specimen by culture or detection of pathogen antigen, nucleic acid sequence, or, for STEC,† Shiga toxin or Shiga toxin genes by a culture-independent diagnostic test (CIDT).§ Listeria infections are defined as isolation of L. monocytogenes or detection of its nucleic acid sequences from a normally sterile site, or from placental or fetal tissue in the instance of miscarriage or stillbirth. Cyclospora infections are defined as detection of the parasite using ultraviolet fluorescence microscopy, specific stains, or polymerase chain reaction.

In this analysis, patients with no history of international travel or unknown travel were considered to have domestically acquired infection.¶ Death was attributed to infection when it occurred during hospitalization or within 7 days after specimen collection for non-hospitalized patients. Incidence (cases per 100,000 population) was calculated by dividing the number of infections in 2020 by the U.S. Census estimates of the surveillance area population for 2019. Incidence measures included all laboratory-diagnosed infections. A negative binomial model with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was used to estimate change in incidence during 2020 compared with those during 2017–2019, adjusting for changes in the population over time.

Surveillance for physician-diagnosed post-diarrheal hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), a complication of STEC infection characterized by renal failure, thrombocytopenia, and microangiopathic anemia, was conducted through a network of nephrologists and infection preventionists and by hospital discharge data review. This report includes HUS data for children aged <18 years for 2019, the most recent year for which data are available. FoodNet surveillance activities were reviewed by CDC and were conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy.**

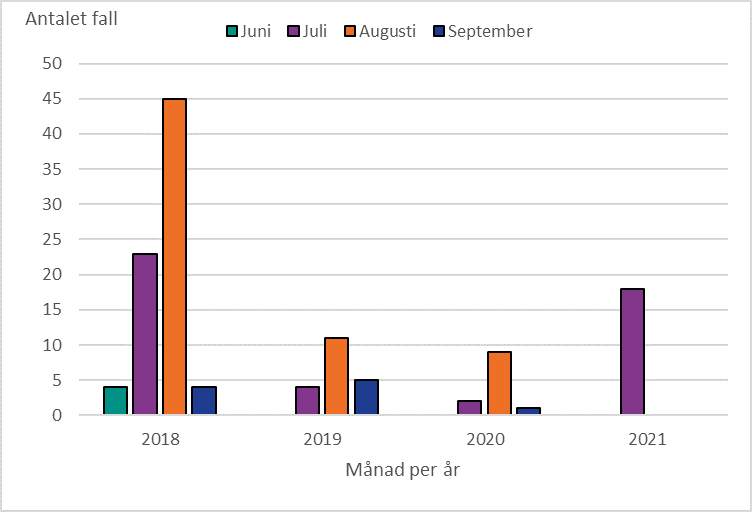

During 2020, FoodNet identified 18,462 cases of infection, 4,788 hospitalizations, and 118 deaths (Table). The overall incidence was highest for Campylobacter (14.4 per 100,000 population), followed by Salmonella (13.3), STEC (3.6), Shigella (3.1), Yersinia (0.9), Vibrio (0.7), Cyclospora (0.6), and Listeria (0.2). During 2020, 26% fewer infections were reported compared with the average annual number reported during 2017–2019; the incidence in 2020 was significantly lower for all pathogens except Yersinia and Cyclospora. The percentage of infections resulting in hospitalization increased 2% compared with 2017–2019 (Figure 1). During 2020, 5% (958) of infections were associated with international travel compared with 14% during 2017–2019. In 2020, most (798; 83%) of these infections occurred during January–March.

Overall, 59% of bacterial infections were diagnosed using a CIDT (range = 14% [Listeria] to 100% [STEC]); this was a 2% increase from 2017−2019. The percentage diagnosed using only a CIDT (i.e., including specimens with negative cultures and those not cultured) was 1% higher during 2020 than the percentage during 2017−2019. Among specimens with a positive CIDT result during 2020, a reflex culture†† was performed for 73%, which was 2% lower than during 2017–2019. Reflex cultures decreased for Vibrio (by 15%), Yersinia (7%), Campylobacter (5%), and STEC (2%); increased for Salmonella (2%), and Shigella (2%); and did not change for Listeria.

Among 5,336 (91%) fully serotyped Salmonella isolates in 2020, the seven most common serotypes were Enteritidis (1.6 per 100,000 population), Newport (1.5), Javiana (1.0), Typhimurium (0.9), I 4,[5],12:i:- (0.5), Hadar (0.4), and Infantis (0.3). Compared with 2017–2019, incidence during 2020 was significantly lower for I 4,[5],12:i:- (48% lower), Typhimurium (37% lower), Enteritidis (36% lower), and Javiana (31% lower). Incidence was significantly higher for Hadar (617% higher; 95% CI = 382–967) and did not change significantly for Newport or Infantis. Most (73%) of the 631 outbreak-associated Salmonella infections during 2020 were caused by three serotypes: Newport (220; 35%), Hadar (135; 21%), and Enteritidis (108; 17%). All outbreak-associated Hadar infections were from one multistate outbreak linked to contact with backyard poultry; 47 (35%) illnesses resulted in hospitalization. Four serogroups accounted for 63% of the 955 culture-positive STEC isolates. Serogroup O157 was most common (264; 28%), followed by O26 (148; 15%), O103 (115; 12%), and O111 (78; 8%).

FoodNet identified 63 cases of post-diarrheal HUS in children aged <18 years (0.6 cases per 100,000 population) during 2019; 55 (87%) had evidence of STEC infection and 41 (65%) were in children aged <5 years (1.4 per 100,000 population). These rates were similar to those during 2016–2018.