CDC

Vegetables are an important part of a healthy diet. Leafy vegetables (called leafy greens on this page), such as lettuce, spinach, cabbage, kale, and bok choy, provide nutrients that help protect you from heart disease, stroke, and some cancers.

But leafy greens, like other vegetables and fruits, are sometimes contaminated with harmful germs. Washing leafy greens does not remove all germs. That’s because germs can stick to the surface of leaves and even get inside them. If you eat contaminated leafy greens without cooking them first, such as in a salad or on a sandwich, you might get sick.

Although anyone can get a foodborne illness, sometimes called food poisoning, some groups of people are more likely to get one and to have a serious illness. These groups include:

- Adults aged 65 and older

- Children younger than 5 years

- People who have health problems or take medicines that lower the body’s ability to fight germs and sickness (a weakened immune system)external icon

- Pregnant people

Eating Leafy Greens

Are leafy greens safe to eat?

Millions of servings of leafy greens are eaten safely every day in the United States. But leafy greens are occasionally contaminated enough to make people sick. To reduce your chance of getting sick, always follow the steps for safely handling and preparing leafy greens before eating or serving them.

Are leafy greens safe for my pet to eat?

Some animals can get sick from some germs that also make people sick. Always follow the steps for safely handling and preparing leafy greens before feeding them to pets and other animals. Never feed recalled food to pets or other animals.

Safely Handling and Preparing Leafy Greens

Do I need to wash all leafy greens?

Prewashed greens don’t need to be washed again. If the label on a leafy greens package says any of the following, you don’t need to wash the greens:

- Ready-to-eat

- Triple washed

- No washing necessary

Prewashed greens sometimes cause illness. But the commercial washing process removes most of the contamination that can be removed by washing.

All other leafy greens should be thoroughly washed before eating, cutting, or cooking.

What is the best way to wash leafy greens?

The best way to wash leafy greens is by rinsing them under running water. Studies show that this step removes some of the germs and dirt on leafy greens and other vegetables and fruits. But no washing method can remove all germs.

Follow these steps to wash leafy greens that you plan to eat raw:

- Wash your hands for 20 seconds with soap and water before and after preparing leafy greens.

- Get rid of any torn or bruised leaves. Also, get rid of the outer leaves of cabbages and lettuce heads.

- Rinse the remaining leaves under running water. Use your hands to gently rub them to help get rid of germs and dirt.

- Dry leafy greens with a clean cloth or paper towel.

Should I soak leafy greens before washing them?

No. Do not soak leafy greens. If you soak them in a sink, germs in the sink can contaminate the greens. If you soak them in a bowl, germs on one leaf can spread to the other leaves. Rinsing leafy greens under running water is the best way to wash them.

Should I wash leafy greens with vinegar, lemon juice, soap, detergent, or produce wash?

Use plain running water to wash leafy greens and other produce. Kitchen vinegar and lemon juice may be used, but CDC is not aware of studies that show vinegar or lemon juice are any better than plain running water.

Do not wash leafy greens or other produce with soap, detergent, or produce wash. Do not use a bleach solution or other disinfectant to wash produce.

What other food safety steps should I keep in mind when I select, store, and prepare leafy greens and other produce?

- Select leafy greens and other vegetables and fruits that aren’t bruised or damaged.

- Make sure pre-cut produce, such as bagged salad or cut fruits and vegetables, is refrigerated or on ice at the store.

- Separate produce from raw meat, poultry, seafood, and eggs in your shopping cart, grocery bags, and refrigerator.

- Store leafy greens, salads, and all pre-cut and packaged produce in a clean refrigerator with the temperature set to 40°F or colder.

- Use separate cutting boards and utensils for produce and for raw meat, poultry, seafood, and eggs. If that isn’t an option, prepare produce before working with raw meat.

- Wash utensils, cutting boards, and kitchen surfaces with hot, soapy water after each use.

- Cook thoroughly or throw away any produce that touches raw meat, poultry, seafood or their juices.

- Refrigerate cooked or cut produce, including salads, within 2 hours (1 hour if the food is exposed to temperatures above 90°F, like a hot car or picnic).

Germs, Outbreaks, and Recalls

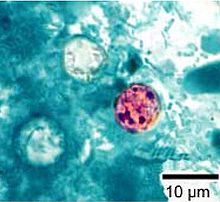

How do leafy greens get contaminated with germs?

Germs that make people sick can be found in many places, including in the soil, in the feces or poop of animals, in refrigerators, and on kitchen surfaces.

Germs can contaminate leafy greens at many points before they reach your plate. For example, germs from animal poop can get in irrigation water or fields where theexternal icon vegetables grow. Germs can also get on leafy greens in packing and processing facilities, in trucks used for shipping, from the unwashed hands of food handlers, and in the kitchen. To prevent contamination, leafy greens should be grown and handled safely at all points from farm to fork.

Read a study by CDC and partners on what we have learned from 10 years of investigating E. coli outbreaks linked to leafy greens.

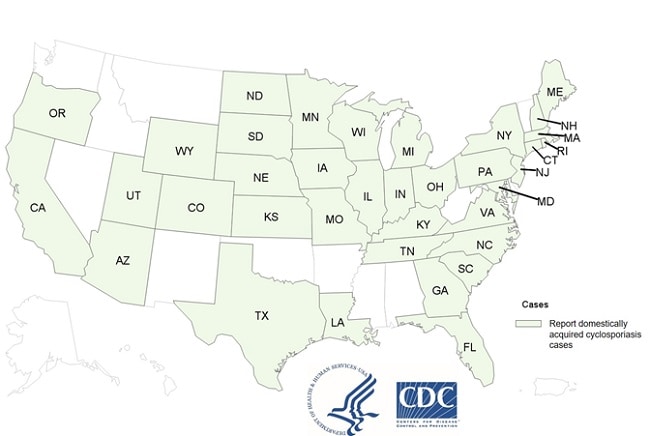

How common are outbreaks linked to leafy greens?

In 2014–2018, a total of 51 foodborne disease outbreaks linked to leafy greens (mainly lettuce) were reported to CDC. Five of the 51 were multistate outbreaks that led CDC to warn the public. Among those five outbreaks, two were linked to packaged salads, two were linked to romaine lettuce, and one could not be linked to a specific type of leafy greens.

Most recently, in 2019–2021, CDC investigated and warned the public about nine multistate outbreaks linked to leafy greens. Among those outbreaks, six were linked to packaged salads, one was linked to romaine lettuce, one was linked to baby spinach, and one could not be linked to a specific type of leafy greens. Learn about these outbreaks.

Most foodborne illnesses are not part of a recognized outbreak. The nearly 2,000 illnesses reported in 2014–2020 outbreaks linked to leafy greens represent only a small part of illnesses caused by contaminated leafy greens during those years.

Does CDC warn the public about every foodborne disease outbreak?

No. CDC does not warn the public about every foodborne outbreak—including ones linked to leafy greens. Some reasons for this include:

- Most sources of foodborne outbreaks are never identified.

- By the time a source is identified, it might no longer be in stores, restaurants, or homes. This can happen with foods that are perishable (foods that spoil or go bad quickly), such as leafy greens.

- Most outbreaks affect people in only one state, so local or state health departments lead the work to identify, investigate, and communicate about those outbreaks. CDC typically communicates only about outbreaks that affect people in more than one state.

Investigating outbreaks linked to leafy greensexternal icon can be especially challenging. These outbreaks often go unidentified or unsolved.

What should I do with leafy greens that are part of a recall?

- Never eat, serve, or sell food that has been recalled, even if some of it was eaten and no one got sick.

- Return the recalled food to the store or throw it away at home.

- Throw out the recalled food and any other foods stored with it or that touched it.

- Put it in a sealed bag in an outside garbage can with a tight lid (so animals cannot get to it).

- If the recalled food was stored in a reusable container, wash the container in the dishwasher or with hot, soapy water.

- Follow CDC’s instructions for cleaning your refrigerator after a food recall.

Organic, Hydroponic, and Home-Grown Leafy Greens

Are organic leafy greens less likely to be contaminated than non-organic ones?

All kinds of produce, including organic leafy greens, can be contaminated with harmful germs at any point from farm to fork. CDC is not aware of any evidence that organic greens are safer.

Learn about some outbreaks linked to organic foodsexternal icon.

Are hydroponic or greenhouse-grown leafy greens less likely to be contaminated?

Leafy greens grown using these methods also can be contaminated with harmful germs at any point from farm to fork.

Learn about an outbreak linked to greenhouse-grown leafy greens.

How do I keep leafy greens in my garden safe to eat?

Home gardens can be an excellent source of fruits and vegetables. Follow these tips to help prevent food poisoning:

- Plant your garden away from animal pens, compost bins, and manure piles.

- Water your garden with clean, drinkable water.

- Keep dirty water, including storm runoff, away from the parts of plants you will eat.

Learn about raised bed gardening pdf icon[PDF – 1 page].

Looking to the Future

What steps are industry and the government taking to make leafy greens safer?

CDC is collaborating with FDA, academia, and industry to investigate the factors that contribute to leafy greens contamination.

The leafy greens industry, FDA, and state regulatory authorities have been implementing provisions of the Produce Safety Ruleexternal icon as part of the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA).external icon They are considering what further measures can be taken. FDA’s 2020 Leafy Greens STEC Action Planexternal icon describes the agency’s plans to work with partners to make leafy greens safer.