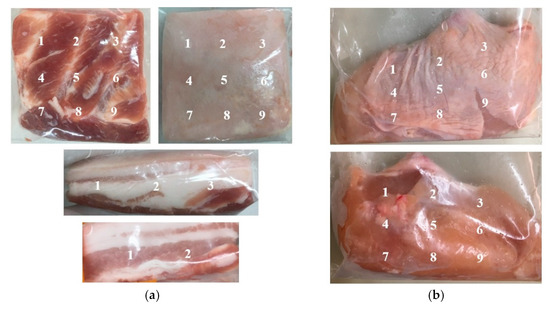

In this research, we aimed to reduce the bacterial loads of Salmonella Enteritidis, Salmonella Typhimurium, Escherichia coli, Campylobacter jejuni, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in pork and chicken meat with skin by applying cold plasma in a liquid state or liquid plasma. The results showed reductions in S. Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium, E. coli, and C. jejuni on the surface of pork and chicken meat after 15 min of liquid plasma treatment on days 0, 3, 7, and 10. However, the efficacy of the reduction in S. aureus was lower after day 3 of the experiment. Moreover, P. aeruginosa could not be inactivated under the same experimental conditions. The microbial decontamination with liquid plasma did not significantly reduce the microbial load, except for C. jejuni, compared with water immersion. When compared with a control group, the pH value and water activity of pork and chicken samples treated with liquid plasma were significantly different (p ≤ 0.05), with a downward trend that was similar to those of the control and water groups. Moreover, the redness (a*) and yellowness (b*) values (CIELAB) of the meat decreased. Although the liquid plasma group resulted in an increase in the lightness (L*) values of the pork samples, these values did not significantly change in the chicken samples. This study demonstrated the efficacy of liquid plasma at reducing S. Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium, E. coli, C. jejuni, and S. aureus on the surface of pork and chicken meat during three days of storage at 4–6 °C with minimal undesirable meat characteristics. View Full-Text